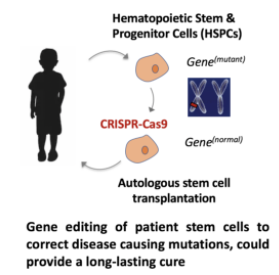

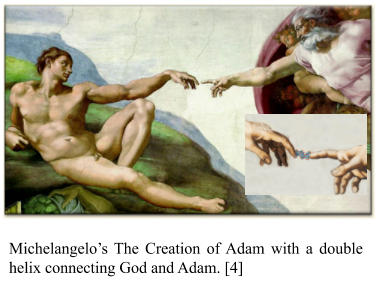

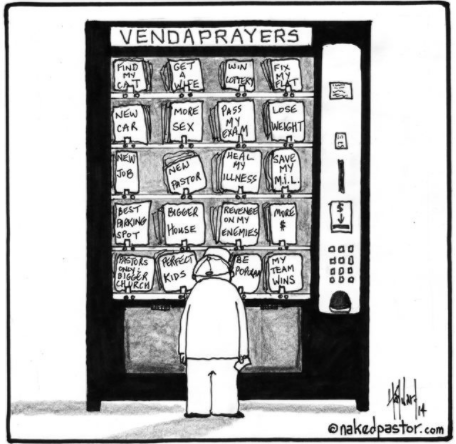

What do you want to be when you grow up? That is a question I’ve been asked time and again and the answer keeps evolving. I’ve gone from being a potato farmer wannabe to wanting to fly a plane after my dad, who is an aircraft engineer. Since saving lives sounds like an interesting job, maybe medicine? The answer to this question became less trivial as I completed high school with decent grades and entered the Singapore army for two years of military service. As I pondered and prayed about my next steps, I gradually felt more drawn to medicine. After all, biology was my favorite subject in school and I loved to learn the intricacies of how bodies are put together. Medicine is an undergraduate degree in Singapore and I began the application process. But somehow after two medical internships, three application cycles, and one failed interview, the doors to medicine shut firmly. As I saw my peers firm up their post-service plans, I became increasingly anxious about what my future held. In April 2011, a few months before college was to start, I was awarded a scholarship to study biochemical engineering at University College London. This is a field that studies how to convert cells into miniature factories producing proteins that we use as medicines - such as insulin for diabetes, or antibodies such as Herceptin to fight cancer. That same week I received this news, my church small group went through Psalm 139 together – God created my inmost being, He perceives my thoughts, and He knows my words even before they are on my tongue. It was this Psalm that gave me reassurance and peace in the face of my hesitation and confusion. I knew that the extent of God’s love for me was displayed on the cross (John 3:16) and that He is a father desiring to give good gifts to His children (Matthew 7:11). But in addition, it was this newfound appreciation that God formed me and knows me more deeply than anyone else does, including myself, that helped me to surrender my uncertainty and entrust my future to Him. I decided to embrace the new door open for me, accept the scholarship, and begin my journey to become a scientist. While it is phrased slightly differently, I realize that the question ‘what do you want to be after ___________ (insert current phase of life or academia) is not going to go away anytime soon but as a follower of Christ, there is a deep abiding peace knowing that a loving and sovereign God who knows the answers and will reveal them in His good time.  From learning how to convert cells into little medicine factories, I became interested in using cells themselves as therapies and joined my current graduate program in Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at Stanford. Stem cells are a special subset of cells in the body that help in regeneration. For example, to replenish ageing red blood cells (RBCs) which have a four-month lifespan, the body produces about 200 billion RBCs every day – that’s about the same order of magnitude as the number of stars in the Milky Way! The source of new RBCs and other immune cells are hematopoietic stem cells, which reside in the bone marrow and last throughout a person’s life. With our understanding of human genetics, many diseases have been attributed to mutations at specific sites in the genetic code of our DNA. Mutations in the hemoglobin gene generate sickle shaped red blood cells that cannot transport oxygen efficiently, leading to sickle cell anemia. Similarly, changes in a gene sequence important for white blood cell development can cause immune disorders such as bubble boy disease. If we can correct gene mutations in patient stem cells and return them to the body, the patient should have a curative source of stem cells producing healthy blood cells. Within the last few years, biologists have learned from nature and developed a tool called CRISPR-Cas9 to precisely cut and insert sequences into a cell’s DNA. I am using this tool to develop a stem cell cure for a genetic autoimmune disease called IPEX syndrome [1]. But with the ability to precisely alter the genetic code, there have been questions of its societal ramifications and whether, from a religious standpoint, researchers are usurping God’s prerogative as Creator. Even before CRISPR technology, the movie Gattaca from 1997 raised such ethical concerns and describes a dystopian society where parents with access to technology can select the type of genes they want their children to have, creating two unequal classes of people in society. In reality, even a simple trait such as eye color is influenced by at least eight genes, and hundreds of genes may influence more complex traits such as height or intelligence. Since we do not fully understand the contribution of each gene to complex human traits and editing multiple genes is a technical challenge, the scenario described in the movie is unlikely. But the fact is that we can now genetically alter a person’s cells and return them to the body. It is also possible to alter the genetic make-up of human embryos that are then implanted, changing their genetic make-up and that of their future offspring.  These questions were important to me as a person of faith and became more urgent when in November 2018, it was announced that a scientist had gone ahead without proper consultation to edit the genomes of two embryos that then were implanted and became two baby girls [2]. While this was widely condemned by the scientific community – mainly on the grounds of the lack of transparency, questionable patient consent, and whether the procedure was a true medical need – it did not provide a satisfying response to the question of whether by making alterations to the code of life, medical researchers like me are ‘playing God’ and have overstepped our roles. I found my answer the following summer in the most unexpected of places while visiting a friend in Washington DC. We visited the US Capitol and one of its wings contains the Brumidi corridors [3] which at first looked like they were covered with standard wallpaper. Upon a closer look, each wall was painted with birds, plants, and scenery from a geological survey of the United States in the 1850s – it was one of the most beautiful insides of a building I’d ever seen! When I walked to the end of that corridor, however, I saw one corner of a wall that was extremely dull. Over hundreds of years, layers of dust had built up and tar from cigarette smoke that was once allowed in the Brumidi corridors stuck to the walls, causing these paintings to lose their original vibrancy. It was only after a restoration project that was completed in 2017 that these paintings began to shine again and the corner I saw had been left in its original state as a comparison.  I found the answer to my question – what I saw at the Capitol that day was a beautiful analogy for the work we are trying to do with CRISPR-Cas9 technology and stem cells, and also with the healthcare profession and medicine more broadly. The role of an art restorer is not to criticize the original masterpiece and change it by re-drawing the posture of the animals or adding new plants to spruce things up – it is merely to restore the painting which was already a masterpiece. It reminded me of a different part of Psalm 139 – that we are fearfully and wonderfully made by God, and our job is to restore those who are sick to live healthy and vibrant lives. Viewing gene editing and regenerative medicine through this new lens has given me a renewed sense of purpose in my work and provided a helpful framework that I use when considering new use cases for CRISPR and other medical technologies. Reflecting back, I see that God did not waste my interest in the field of medicine; he was using it in a different way. My vocation is training me to use science to help advance the field of medicine – which was something I did not appreciate when I faced rejection from medical school. God is not a vending machine for which, if I put in the correct format and length of prayer, the results I want are assured. We can plan our lives in a certain way, but it is God who determines our steps (Proverbs 16:9). I encourage you to trust Him because He is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to His power that is at work within us (Ephesians 3:20-21). If these themes resonated with you or you have more questions on gene editing and its implications, I would love to chat so please reach out to me at [email protected] Vendaprayers [5] References:

[1] Goodwin, M., Lee, E., Lakshmanan, U., Shipp, S., Froessl, L., & Barzaghi, F. et al. (May 2020). CRISPR-based gene editing enables FOXP3 gene repair in IPEX patient cells. Science Advances, 6(19), eaaz0571. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz0571 [2] Dennis Normile Chinese scientist who produced genetically altered babies sentenced to 3 years in jail. (Dec 30, 2019). Retrieved 15 August 2020, from https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/12/chinese-scientist-who-produced-genetically-altered-babies-sentenced-3-years-jail [3] Brumidi Corridors, Architect of the Capitol. (2020). Retrieved 15 August 2020, from https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/buildings-grounds/capitol-building/senate-wing/brumidi-corridors\ [4] Karlee R (Dec 21 2018) A doctored version of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam newly features a double helix connecting God and Adam, Emergent Concepts in New Media Art, Medium, Retrieved 16 August 2020, from https://medium.com/emergent-concepts-in-new-media-art/self-perception-28dbe9696ae0 [5] David Hayward (January 22 2014) If only pryer was this easy!, Retrieved 16 August 2020, from https://www.patheos.com/blogs/nakedpastor/2014/01/if-only-prayer-was-this-easy/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorContributions are from various grad students throughout our area. There are a wide variety of thoughts and beliefs within our community, but we strive together to engage in reflective conversation with the common goal to seek Jesus. Archives

March 2021

Categories |

|

Copyright © InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed