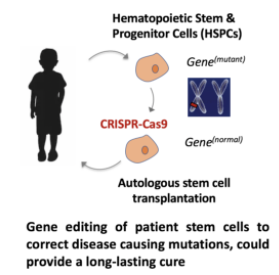

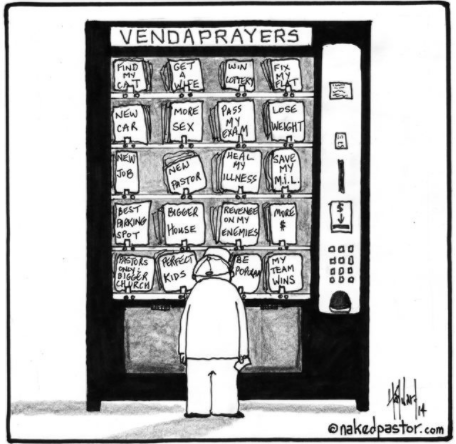

What do you want to be when you grow up? That is a question I’ve been asked time and again and the answer keeps evolving. I’ve gone from being a potato farmer wannabe to wanting to fly a plane after my dad, who is an aircraft engineer. Since saving lives sounds like an interesting job, maybe medicine? The answer to this question became less trivial as I completed high school with decent grades and entered the Singapore army for two years of military service. As I pondered and prayed about my next steps, I gradually felt more drawn to medicine. After all, biology was my favorite subject in school and I loved to learn the intricacies of how bodies are put together. Medicine is an undergraduate degree in Singapore and I began the application process. But somehow after two medical internships, three application cycles, and one failed interview, the doors to medicine shut firmly. As I saw my peers firm up their post-service plans, I became increasingly anxious about what my future held. In April 2011, a few months before college was to start, I was awarded a scholarship to study biochemical engineering at University College London. This is a field that studies how to convert cells into miniature factories producing proteins that we use as medicines - such as insulin for diabetes, or antibodies such as Herceptin to fight cancer. That same week I received this news, my church small group went through Psalm 139 together – God created my inmost being, He perceives my thoughts, and He knows my words even before they are on my tongue. It was this Psalm that gave me reassurance and peace in the face of my hesitation and confusion. I knew that the extent of God’s love for me was displayed on the cross (John 3:16) and that He is a father desiring to give good gifts to His children (Matthew 7:11). But in addition, it was this newfound appreciation that God formed me and knows me more deeply than anyone else does, including myself, that helped me to surrender my uncertainty and entrust my future to Him. I decided to embrace the new door open for me, accept the scholarship, and begin my journey to become a scientist. While it is phrased slightly differently, I realize that the question ‘what do you want to be after ___________ (insert current phase of life or academia) is not going to go away anytime soon but as a follower of Christ, there is a deep abiding peace knowing that a loving and sovereign God who knows the answers and will reveal them in His good time.  From learning how to convert cells into little medicine factories, I became interested in using cells themselves as therapies and joined my current graduate program in Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at Stanford. Stem cells are a special subset of cells in the body that help in regeneration. For example, to replenish ageing red blood cells (RBCs) which have a four-month lifespan, the body produces about 200 billion RBCs every day – that’s about the same order of magnitude as the number of stars in the Milky Way! The source of new RBCs and other immune cells are hematopoietic stem cells, which reside in the bone marrow and last throughout a person’s life. With our understanding of human genetics, many diseases have been attributed to mutations at specific sites in the genetic code of our DNA. Mutations in the hemoglobin gene generate sickle shaped red blood cells that cannot transport oxygen efficiently, leading to sickle cell anemia. Similarly, changes in a gene sequence important for white blood cell development can cause immune disorders such as bubble boy disease. If we can correct gene mutations in patient stem cells and return them to the body, the patient should have a curative source of stem cells producing healthy blood cells. Within the last few years, biologists have learned from nature and developed a tool called CRISPR-Cas9 to precisely cut and insert sequences into a cell’s DNA. I am using this tool to develop a stem cell cure for a genetic autoimmune disease called IPEX syndrome [1]. But with the ability to precisely alter the genetic code, there have been questions of its societal ramifications and whether, from a religious standpoint, researchers are usurping God’s prerogative as Creator. Even before CRISPR technology, the movie Gattaca from 1997 raised such ethical concerns and describes a dystopian society where parents with access to technology can select the type of genes they want their children to have, creating two unequal classes of people in society. In reality, even a simple trait such as eye color is influenced by at least eight genes, and hundreds of genes may influence more complex traits such as height or intelligence. Since we do not fully understand the contribution of each gene to complex human traits and editing multiple genes is a technical challenge, the scenario described in the movie is unlikely. But the fact is that we can now genetically alter a person’s cells and return them to the body. It is also possible to alter the genetic make-up of human embryos that are then implanted, changing their genetic make-up and that of their future offspring.  These questions were important to me as a person of faith and became more urgent when in November 2018, it was announced that a scientist had gone ahead without proper consultation to edit the genomes of two embryos that then were implanted and became two baby girls [2]. While this was widely condemned by the scientific community – mainly on the grounds of the lack of transparency, questionable patient consent, and whether the procedure was a true medical need – it did not provide a satisfying response to the question of whether by making alterations to the code of life, medical researchers like me are ‘playing God’ and have overstepped our roles. I found my answer the following summer in the most unexpected of places while visiting a friend in Washington DC. We visited the US Capitol and one of its wings contains the Brumidi corridors [3] which at first looked like they were covered with standard wallpaper. Upon a closer look, each wall was painted with birds, plants, and scenery from a geological survey of the United States in the 1850s – it was one of the most beautiful insides of a building I’d ever seen! When I walked to the end of that corridor, however, I saw one corner of a wall that was extremely dull. Over hundreds of years, layers of dust had built up and tar from cigarette smoke that was once allowed in the Brumidi corridors stuck to the walls, causing these paintings to lose their original vibrancy. It was only after a restoration project that was completed in 2017 that these paintings began to shine again and the corner I saw had been left in its original state as a comparison.  I found the answer to my question – what I saw at the Capitol that day was a beautiful analogy for the work we are trying to do with CRISPR-Cas9 technology and stem cells, and also with the healthcare profession and medicine more broadly. The role of an art restorer is not to criticize the original masterpiece and change it by re-drawing the posture of the animals or adding new plants to spruce things up – it is merely to restore the painting which was already a masterpiece. It reminded me of a different part of Psalm 139 – that we are fearfully and wonderfully made by God, and our job is to restore those who are sick to live healthy and vibrant lives. Viewing gene editing and regenerative medicine through this new lens has given me a renewed sense of purpose in my work and provided a helpful framework that I use when considering new use cases for CRISPR and other medical technologies. Reflecting back, I see that God did not waste my interest in the field of medicine; he was using it in a different way. My vocation is training me to use science to help advance the field of medicine – which was something I did not appreciate when I faced rejection from medical school. God is not a vending machine for which, if I put in the correct format and length of prayer, the results I want are assured. We can plan our lives in a certain way, but it is God who determines our steps (Proverbs 16:9). I encourage you to trust Him because He is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to His power that is at work within us (Ephesians 3:20-21). If these themes resonated with you or you have more questions on gene editing and its implications, I would love to chat so please reach out to me at [email protected] Vendaprayers [5] References:

[1] Goodwin, M., Lee, E., Lakshmanan, U., Shipp, S., Froessl, L., & Barzaghi, F. et al. (May 2020). CRISPR-based gene editing enables FOXP3 gene repair in IPEX patient cells. Science Advances, 6(19), eaaz0571. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz0571 [2] Dennis Normile Chinese scientist who produced genetically altered babies sentenced to 3 years in jail. (Dec 30, 2019). Retrieved 15 August 2020, from https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/12/chinese-scientist-who-produced-genetically-altered-babies-sentenced-3-years-jail [3] Brumidi Corridors, Architect of the Capitol. (2020). Retrieved 15 August 2020, from https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/buildings-grounds/capitol-building/senate-wing/brumidi-corridors\ [4] Karlee R (Dec 21 2018) A doctored version of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam newly features a double helix connecting God and Adam, Emergent Concepts in New Media Art, Medium, Retrieved 16 August 2020, from https://medium.com/emergent-concepts-in-new-media-art/self-perception-28dbe9696ae0 [5] David Hayward (January 22 2014) If only pryer was this easy!, Retrieved 16 August 2020, from https://www.patheos.com/blogs/nakedpastor/2014/01/if-only-prayer-was-this-easy/

0 Comments

By Nathan Wei Ph.D. Candidate, Mechanical Engineering, Stanford University What is the world’s most epic story? One might argue for Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Perhaps it’s the Iliad, or the Epic of Gilgamesh. What about Shakespeare? Star Wars? War and Peace? The Marvel Cinematic Universe? As captivating as they are, a Christian perspective might suggest that all of these grand tales are simply faint reflections of the ultimate story of God’s work in the world. In classic Hollywood fashion, this is often framed as a trilogy: creation, fall, and redemption.1 For Christians, this is the most comprehensive story imaginable: it’s God’s story, our story, and the story of the entire course of history, all rolled into one magnificent, massive metanarrative.2 Accordingly, we can get pretty jazzed about the things God is doing on a cosmic scale: singing songs, shouting praises, celebrating holidays. But more often, that bigger picture feels far removed from the mundane routines of daily life: sending emails, attending meetings, doing laundry. Is there a way to bridge the gap? Can we relate our individual stories to God’s big story? The Concept of Square-Inch Stories Enter the square-inch story.3 The name draws inspiration from the declaration of Dutch theologian Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920): “No single piece of our mental world is to be hermetically sealed off from the rest, and there is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, ‘Mine!’”4 In this powerful proclamation, Kuyper emphatically erases the gap between our activities and God’s plans. While Christ reigns over the entire arc of human history, He also rules over every single square inch we inhabit.5 These square inches include our work, our vocation, our passions, our hobbies, our relationships, our communities, and our worldviews. Kuyper reminds us that Christ cares deeply about each and every one of these areas, as each has an immeasurably important part to play in His story.6 A square-inch story aims to actualize Kuyper’s vision by selecting one particular square inch and seeking to understand how it is connected with God’s greater plan. First, it identifies key patterns, processes, and philosophies within the square inch. It then critically examines these elements in light of the ultimate story, discerning which parts are good (creation), and which parts have been corrupted (fall). Finally, it reimagines these pieces as tools and materials for the building up of God’s kingdom (redemption). A square-inch story thus conveys a domain-specific expression of Christ’s vision for the renewal of all things. Before we consider how to put together a square-inch story, we should clarify why this complicated endeavor is worth our time. I offer three motivations: personal, ecclesial, and missional.7 First, on a personal level, the process of thinking through our disciplines helps us discover meaning and purpose within the seemingly mundane activities we perform in our square inches. This can strengthen our faith and help us submit all areas of our life to God’s will.8 Secondly, the Church is constantly in need of thoughtful narratives of reconciliation that restore square inches to proper relationship with the Body of Christ. For example, widely circulated stories about the incompatibility of Christian faith with the natural and social sciences have left many Christians suspicious of modern science. What would it look like if instead we told stories of the designated role of science in God’s redemptive plan?9 Finally, square-inch stories are inherently missional, because every story has the potential to connect with people in unique and meaningful ways.10 Since the Body of Christ is by design wonderfully diverse, each Christ-follower inhabits a different set of communities.11 Each of us therefore is uniquely positioned to engage with a particular group of people, as ambassadors of Christ to a particular square inch.12 The square-inch story helps us step into this role, by identifying areas of common ground with our neighbors and colleagues 13 and giving us the framework and vocabulary to tell God’s story in the language of the square inch.14 In accordance with its missional orientation, the structure of a square-inch story will largely be determined by the particular characteristics of the community it addresses. It may lean philosophical or practical, intellectual or relational. It may take the form of a talk, a blog post, a painting, or a composition. The specifics are up to the storyteller, but in all cases, the content is centered on connections between the square inch and the overarching metanarrative. The Construction of Square-Inch Stories We thus return to the practical question: how do we put together a square-inch story? As we have seen, the square-inch story draws substance from the three-part structure of the ultimate story. We can therefore begin thinking through our square inches by looking at their assumptions and practices through the lens of the story of Scripture, or in the words of Dr. Chris Watkin, “letting the Bible set its own table.”15 Creation. As in the ultimate story, we expect to find elements within our square inches that are inherently good and bear the hallmarks of God’s design. These can and should be affirmed and celebrated, such as the beauty of music or the intricacies of DNA. In this sense, the construction of a square-inch story is a process of exploration that leads to awe and worship.16 Fall. However, we should not be surprised to find areas within our square inches that have fallen away from God’s good plan. These often take the form of implicit assumptions embedded in the philosophy of a discipline that only become visible under the spotlight of Scripture. In many cases, these assumptions lie at the roots of systemic blind spots and unjust patterns of thought and action. The construction of a square-inch story is thus a critical endeavor that exposes the brokenness in a square inch and highlights its need for redemption.17 Redemption. With this brokenness as a backdrop, a square-inch story can ask how Christ will redeem the fallen aspects of the square inch and transform it into a place of worship, justice, and human flourishing.18 How can this field glorify God? How can this discipline seek justice and love mercy?19 How is Christ calling this community to serve those in need? There are no easy answers to these questions, but as we wrestle with them, we begin to see how our little square inch fits into God’s grand plan to make all things work together for good.20 The Continuation of Square-Inch Stories Creating a square-inch story requires a significant investment of thought and reflection, and it is not a project to tackle alone. Kuyper himself, referring to the academic application of square-inch theology, said that this is a “task which surpasses our human strength.”21 It requires wisdom from the Holy Spirit, guidance from Scripture, and support, encouragement, and correction from Christian community. Furthermore, the construction of a square-inch story does not end with the completion of an article or talk. It is a lifelong process that we undertake for every square inch we find ourselves in, and our work is not complete until the whole domain of human existence sits obediently before the throne of God. With this humbling perspective in mind, I shall close in the great academic tradition of pointing to future work. In the square-inch stories that follow in this series, you will see a variety of explorational forays into the Kuyperian enterprise – square-inch seedlings, if you will, putting down roots into their particular disciplines and communities, and stretching themselves upward toward the light of Christ. You will hear from students and scholars who are learning to become better storytellers and translators for their colleagues and contemporaries. And I hope you will be inspired by their testimonies to take a closer look at the domains you engage with – because every square inch has an indispensable role to play in the world’s most epic story. Recommended Resources

Many thanks to Andrea Chaikovsky, Carissa Wei, Jonathan Love, Joy Chiew, Katie Ferrick, and Kristel Tjandra for providing feedback on this article, and to the members of the Stanford IVGrad Square-Inch Discussion Group for collectively shaping the vision for this project. Footnotes: 1 Trevin Wax, Counterfeit Gospels: Rediscovering the Good News in a World of False Hope (2011). Wax adds a fourth and final element, restoration (or consummation), which is ‘beyond the scope of this work.’ 2 A metanarrative is an overarching story that serves as a framework for the interpretation of ideas or events. 3 “Square-centimeter story” is scientifically more correct, but it doesn’t roll off the tongue quite as nicely. 4 Abraham Kuyper, “Sphere Sovereignty” (1880). Address at the Free University of Amsterdam. Translation available here. 5 Kuyper called these “spheres”, but to be metaphorically and geometrically consistent, I conflate his idea of sphere sovereignty with the square-inch declaration quoted above. The man himself inhabited several of these spheres, as a theologian, journalist, academic, politician, and statesman. See this blog post for a more detailed discussion. 6 This idea did not necessarily originate with Kuyper. For instance, the English bishop Joseph Hall (1574-1656) is noted for saying with regard to secular work that “God loveth adverbs; and cares not how good, but how well” (cf. Nicholas Wolterstorff, Educating for Shalom, p. 270). 7 Tish Harrison Warren, in her contribution to Uncommon Ground: Living Faithfully in a World of Difference (Timothy Keller and John Inazu, eds.), writes, “This intentional practice of, in the words of Luci Shaw, “telling and retelling the story that weaves together divine transcendence and earthly human experience” shapes us as believers, and it shapes our readers” (p. 80). Her essay underscores the importance of communication: “our words shape our practices, just as practices shape our words” (p. 80). 8 Colossians 3:17. It is also worthwhile to consider reason and critical thinking as spiritual disciplines. Enoch Kuo (who first introduced me to Kuyper) elaborates on this idea in this blog post. He draws from Mike Higton’s A Theology of Higher Education, which is a useful reference for this topic and for Christian engagement in a university context. 9 An excellent example of this kind of story is The Language of God by Dr. Francis Collins. 10 An emphasis on stories is increasingly relevant as our society transitions from a postmodernist worldview to a “metamodernist” one, in which meta-narratives are empowered as catalysts for progress and unity. In this philosophical landscape, the square-inch story becomes even more crucial to maintaining an effective Christian witness. 11 Dr. Katharine Hayhoe, a renowned climate scientist and outspoken evangelical Christian, frequently emphasizes the influence we can have on the individual communities we find ourselves in. Here, she discusses this in relation to environmental advocacy, but her ideas are readily generalizable. 12 2 Corinthians 5:18-20. 13 Acts 17:22-34. 14 Acts 2:6-12. For a much more comprehensive discussion of the Christian’s role as translator, see John Inazu’s essay in Uncommon Ground. 15 Dr. Chris Watkin was our invited speaker at the annual InterVarsity NorCal Grad Student Winter Conference in January 2020. His talks provided the inspiration, vocabulary, and theological framework for this project. Links to the talks can be found on his blog, “Thinking Through the Bible.” 16 There is great precedent for this in Scripture (e.g. Psalm 19:1-6, Proverbs 30:24-28), as well as in the history of Christian thought. In my own research, I am constantly in awe of the intricate motions of fluid flows and the mathematical concept of chaos, both of which are powerful recurring themes in the Bible. 17 Nicholas Wolterstorff writes that Christians should “nourish critique that is shaped by the hopes and memories of the biblical narrative, including then, ethical critique of the practices of society generally” (Educating for Shalom, p. 130). This critique is driven by “the faces and voices of those suffering in our world”, since “an ethic that does not echo humanity’s lament does not merit humanity’s attention” (p. 133). 18 This perspective of Christian engagement with aspects of secular culture reflects H. Richard Niebuhr’s paradigm of “Christ transforming culture” from his influential book Christ and Culture (1951). In the wise words of Wolterstorff: "To serve God faithfully and to serve humanity effectively, one has to critique the received role [i.e. our square inch] and do what one can to alter the script" (Educating for Shalom, p. 272). 19 Micah 6:8. 20 Ephesians 1:9-10. 21 Abraham Kuyper, “Sphere Sovereignty.” |

AuthorContributions are from various grad students throughout our area. There are a wide variety of thoughts and beliefs within our community, but we strive together to engage in reflective conversation with the common goal to seek Jesus. Archives

March 2021

Categories |

|

Copyright © InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed