Officer: Hi, welcome to the UCSF lost and found, how may I help you today?

0 Comments

Christian Integrity in Academia | Evan Laksono, Ph.D Student in Applied Physics, Stanford University1/5/2021  A reflection on Christian integrity is highly important for Christians who seek to be salt and light in the world and become a faithful witness for the Gospel. It is a desirable quality Christians should pursue if we take the Scripture seriously (see Prov. 11:3, 19:1, 29:7). With a stark reminder of the recurring failures of the church to uphold the message that she proclaims (1), we should focus and discipline ourselves in pursuing Christian integrity. In this blogpost, I will try to sketch some aspects of Christian integrity and discuss some possible applications for Christians in secular academia. The meaning and nature of Christian integrity Integrity points to the quality of completeness, wholeness, uprightness or perfection (2). There is no dissonance between a person’s thoughts, emotions and actions when they face different circumstances. There is also a consistency between a person’s public and private identities. As Christians who take seriously the Lordship of Christ over our lives, we cannot shy away from wrestling with integrity since God demands our utmost and total devotion (Mat. 22:37-40). I would suggest that Christian integrity means consistency between our way of life (3) and our given identity rooted in God’s call (4, 5). Firstly, note that Christian integrity flows out of God’s call, which marks its distinct nature from the notion of integrity which is not exclusive to Christianity. It is also not an identity of our own choice, but a given identity (6) which requires obedience. We should not miss how countercultural the idea is. In a secular and individualistic Western culture, we are accustomed to thinking that we are free to choose our way of life and that we are in charge of our own identity. It is easy to turn self-actualization into the goal of our life pursuits (7). There are also plenty of opportunities to become whatever we fashion ourselves to be. Coupled with our innate tendency to cling to power and control, it becomes increasingly difficult for Christians to pay attention and respond to the Caller. Christian integrity stands in diametric opposition to self-determination. Instead, it demands Christians to overcome this fallen tendency as we strive to live with the posture of faith because our goal is to please God (Heb. 11:6). Christian integrity also means our way of life is fully shaped by the gospel that we profess. We do not only proclaim the gospel which culminates in the cross, but also embody the gospel and the cross in the way we live. As we make Christlikeness our goal in our spiritual growth, we also strive to emulate Christ, who “emptied himself” and “humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross” (Phil. 2:7-8). Undoubtedly, this is a radical idea. Yet, Christ himself did not sugarcoat His call as He said that, “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me.” (Mat. 16:24). A life shaped by the gospel will be increasingly characterized by self-giving love, readiness to overcome evil with good, patient endurance, self-understanding, self-affirmation, joyful obedience, mature holiness and hope for glory (8). Clearly, the demand of Christian integrity is very high. An honest and critical examination about the way we live can always reveal our own shortcomings. As Christians are endowed with a capacity to know ourselves before God, our eyes can see beyond our innate pride that we are fallen human beings. Our grasp of the gospel paradoxically leads to an essential element of Christian integrity, that we recognize and acknowledge our own shortcomings to live up to God’s demand for integrity (9). To put it differently, Christian integrity, in its most comprehensive sense, is elusive. The reason is found in the gospel, which sheds light on our conditions that we are sinners before God. However, through the gospel, we have also tasted God’s salvation freeing us from the bondage of sins, so that by His grace we can be bold in pursuing a life increasingly characterized by Christian integrity. Application for Christians in academia We can now reflect on what Christian integrity might look like for Christians in academia. I found it helpful to think about our engagement in academia in terms of the following categories: contact (relationship with other academic members), context (how to approach our work) and content (the subject matter of our discipline) (10). These are three areas in which we should be prepared to engage with. The emphasis put on each of these categories would also change throughout a person’s academic career. During our early days in the academia as PhD students, we are probably not in the position to shape the content from a Christian perspective. It will be a time for us to understand our discipline at a greater depth and explore some potential areas for Christian engagement. However, we can pursue Christian integrity in the areas of contact and context. For example, we can make ourselves available to our colleagues instead of burning all of our time for research work since we seek to extend God’s love for them. Refraining from gossip, we might instead offer a different perspective towards PhD life when corrupt talks that demean professors or promote cynicism are prevalent. In the area of context, we can demonstrate Christian integrity by being transparent about the status of our research when it might not be what our supervisors or collaborators expect to hear. Exercising integrity in financial matter might mean that we refrain from claiming reimbursements more than our actual expenses. The challenge does not get easier as we become senior researchers or young professors. In the academic world with ‘publish or perish’ mantra, it might be tempting to dedicate all our efforts only to pursue more high-profile publications which are necessary to secure well-paid faculty jobs. Nevertheless, at this career stage we should be prepared to be Christian witnesses by engaging with substantial issues concerning our disciplines. For example, we should be prepared to critique the dominant narratives defining our fields, if they align with the vision of the Kingdom to bring shalom (11) upon the world. When we are called to speak in an academic or a church context, we should also guard ourselves from developing a dualistic life, such as by devising our speech according to the audience in order to avoid the risk of objection or even rejection (12). Christian integrity also means we come up with a different set of priorities when we discern our vocations as we seek to live according to the gospel. We are willing to honestly evaluate if our routines and decisions truly serve God’s purposes in the world and address tough questions. For example, will we willingly serve the communities in which God places us when it does not give us direct benefits even as the demands for academic publication increase? Will we make room for ourselves to grow in our Scriptural understanding so that we are prepared to testify about our faith and its influence on our learning and practice to our academic colleagues, while making a consistent testimony to the church? Are we open to the possibility that God might call us to serve as faculties in lesser institutions, where our roles potentially bring greater transformative effect to the community? Concluding Remarks There is no neat formula for Christians to ensure our lives are marked by Christian integrity. The best bet seems to be a continual effort to leverage every opportunity to develop essential character traits for Christian integrity, such as humility and courage. Therefore, we should watch and examine carefully the way we live day by day. We should also seriously learn from the Scripture so that we grow in our understanding of what it means to lead a life “worthy of the gospel of Christ” (Phil 1:27). Cultivating Christian integrity is simply not a matter to be left for the future. The task of becoming academics who live with Christian integrity is daunting as we reflect carefully what might come before us. In its pursuit, there might be a time when we have to face uncertainties, challenges or failures. It might be difficult to pursue it alone, but we should remember that we are not alone in the journey. It is thus important to get rooted in a Christian community to spur our growth in Christ and support us to live with Christian integrity. When we face uncertainties, stand on what we can be sure about, that God is faithful and gracious to grant us wisdom (Jas. 1:5) and “teach the humble His way” (Ps. 25:9). When challenges come, we should remember that we have received costly grace (13). When we fail to live with integrity, we can confess our sins and ask God for His grace to forgive and sanctify us (1 Jn. 1:9). God’s grace is not powerless. It is the most important resource that will empower us to walk with integrity in order to fulfill His calling for us in academia. Acknowledgement I would like to thank Kristel Tjandra, Andrea Chaikovsky and Nathaniel Wei, who have provided invaluable inputs for this blogpost. I am indebted to them for their willingness to read this piece carefully and thoughtfully. I am delighted to present the draft of this post to Adrian Nugroho, my undergraduate mentor, who has also commented on the post. Recommended readings:

Footnotes:

UCSF lost and found

I don’t know when it began, but happened gradually as the first fall quarter unfolded. First, I began by picking up little pieces that people left behind. Pipette tips from the post doc as he hurried from one end of the corridor to another; colourful tablets left by the nurse as she headed for a quick lunch at the Moffit; the latest line of the new R01 the new assistant professor was writing. Just little things that were on people’s minds as they bustled about their day. Don’t pick them up, I was told, they will get grimy in your hands. But I did anyway. Little bits and pieces from people’s days, kept in a box tucked away only for me to enjoy. They started to fade over time, but it was fine as long as I could recognize it.

Soon, I started to progress to bigger things. Things from lunch conversations and the latest gossip between labs. “Did you hear? JJ Lee just published another paper!” “Aries Mandy just won her first grant despite passing her quals a month ago.” These pieces that fell from conversations were much more substantial. I kept them too. They held up slightly better than the little bits I used to collect. The box became too small to hold them. I started to piece these things together on my shelf. However, these pieces didn’t always fit together nicely. How good are these high achievers? Where did they come from and what else have they accomplished? Without these questions answered, I didn’t have the glue. I hopped on the internet and began to search. And search and search, until I found the connections I needed. LinkedIn, ResearchGate, Google Scholar, yes, even Facebook and Twitter. Not just fragments of conversations, but now whole stories, webpages even. Pictures of cake and champagne on Facebook for a job well done. A new tweet on the latest publication. A smug new paper that boosted a ResearchGate score by 3 points. The rest of the connections I didn’t have, I realized I could start producing my own glue too to fill in the gaps. The finer details, I personally molded by hand. My little sculpture migrated to my table, sitting ominously on it like an altar. The perfect graduate student had been made. The aspiration I bowed down to every time I used my laptop. Then, I looked at the mirror, and realized I was nothing like it. Those perfect hands that pipetted everything accurately and coded everything with scary efficiency, compared to my feeble, shaky ones. Those eyes that could see clearly, every little detail in a figure. Unlike mine that were myopic, I needed glasses and still couldn’t spot the errors. That perfect pair of feet, that never got tired despite working a full 24 hours. I feel a wave of guilt as I remember dropping a test tube rack and spilling all my samples just the night before. A wave of panic rose within me. How did I even get here and do I deserve to be here? Why am I not enough? I began to look for sacrifices, placing my calendar and sleep schedule on the altar. Yet, the more I did, the more it demanded. More stories were added to upkeep its appearances, and no matter how hard I worked, I could never keep up. Then I remembered. It was all just my creation, the altar of the perfect student I needed to be. It was mute and dumb with no actual power, just fragments of the things that I had amassed. Some of the pieces no longer looked like their original forms. I mustered up my courage and broke it with a hammer into many pieces. May you never torment another grad student again! The space on my desk now sat with a stark emptiness. I needed to act, lest it be filled up again with another altar of achievement. I began to piece together words I should have held on to from the start. “Fearfully and wonderfully made. Loved. Worthy.” Today, I drop these words too as I go about my day. Little tidbits for others who are collecting pieces from the people around them, trying to make sense of grad school. I came to the United States earlier this year not knowing much about the history of this country and the dynamics of various people groups in America. The tragic deaths of George Floyd, Ahmed Arbery, and many others before and after, soon awakened my awareness of the issue of injustice that is crawling beneath the façade of this nation. As a citizen of a Universe-ity (and I say this because our campuses are melting pots of global citizens), I feel the weight of responsibility to reflect on my own racial blindness and discrimination.

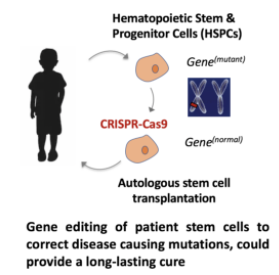

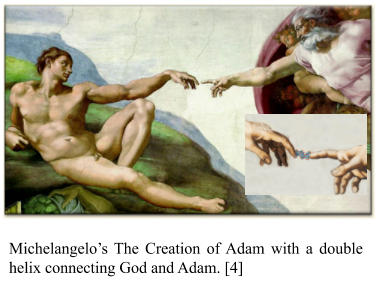

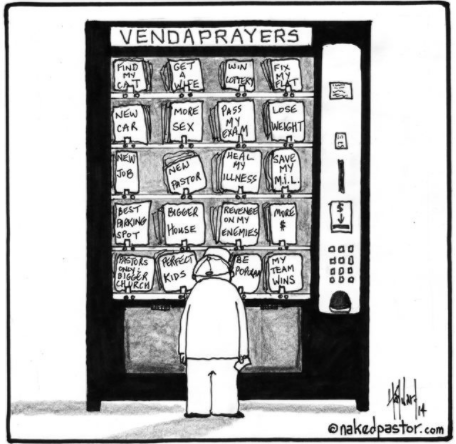

As a third-generation Chinese immigrant, I have experienced life as a minority and witnessed first-hand the pain of unbelonging. But this experience doesn’t justify any slothful involvement towards justice and equality. As someone who is currently involved in academic work, I dream that one day my class will be full of people from different nations, colors, and tongues learning and interacting in harmony. I aspire that there will be deep respect and honor for one another. We do not choose the colour of our own skin, but how we see colors and what we do with our perceptions are decisions we need to make every single day. Most importantly, as a Christian, I believe that every individual bears the image of God –an identity that comes with dignity and responsibility. Therefore, our personhood is a color of its own in a spectrum of humanity. Everyone has a place in it and everyone contributes to its beauty. I wouldn’t say that I have found the solution for inclusivity within my square inch, but one thing that came out of my ongoing reflection is to discipline myself to reach out to those who are different to me. Conversations are the starting point. Dr. Bryan Stevenson, a proponent of the Equal Justice Initiatives, once said that we need to "get proximate, to change the narrative, to stay hopeful, and to do uncomfortable things." The wonderful thing about being a Christian is that we can do this as a community. My exhortation for all of us is to help each other and keep each other accountable in our journey towards this vision. For more about my reflection on how we can do justice, love mercy and walk humbly in the University, check out my article published on Stanford Vox Clara. Dr. Kristel C. Tjandra is a Postdoctoral Scholar in the School of Medicine at Stanford University. She obtained her doctorate degree in Australia. Her research interests span the field of nanomedicine, drug delivery, medicinal chemistry, and disease diagnostics. Apart from conducting experiments, she enjoys engaging in science communication, community outreach and education. She is also a part of the IVGrad ministry at Stanford.  What do you want to be when you grow up? That is a question I’ve been asked time and again and the answer keeps evolving. I’ve gone from being a potato farmer wannabe to wanting to fly a plane after my dad, who is an aircraft engineer. Since saving lives sounds like an interesting job, maybe medicine? The answer to this question became less trivial as I completed high school with decent grades and entered the Singapore army for two years of military service. As I pondered and prayed about my next steps, I gradually felt more drawn to medicine. After all, biology was my favorite subject in school and I loved to learn the intricacies of how bodies are put together. Medicine is an undergraduate degree in Singapore and I began the application process. But somehow after two medical internships, three application cycles, and one failed interview, the doors to medicine shut firmly. As I saw my peers firm up their post-service plans, I became increasingly anxious about what my future held. In April 2011, a few months before college was to start, I was awarded a scholarship to study biochemical engineering at University College London. This is a field that studies how to convert cells into miniature factories producing proteins that we use as medicines - such as insulin for diabetes, or antibodies such as Herceptin to fight cancer. That same week I received this news, my church small group went through Psalm 139 together – God created my inmost being, He perceives my thoughts, and He knows my words even before they are on my tongue. It was this Psalm that gave me reassurance and peace in the face of my hesitation and confusion. I knew that the extent of God’s love for me was displayed on the cross (John 3:16) and that He is a father desiring to give good gifts to His children (Matthew 7:11). But in addition, it was this newfound appreciation that God formed me and knows me more deeply than anyone else does, including myself, that helped me to surrender my uncertainty and entrust my future to Him. I decided to embrace the new door open for me, accept the scholarship, and begin my journey to become a scientist. While it is phrased slightly differently, I realize that the question ‘what do you want to be after ___________ (insert current phase of life or academia) is not going to go away anytime soon but as a follower of Christ, there is a deep abiding peace knowing that a loving and sovereign God who knows the answers and will reveal them in His good time.  From learning how to convert cells into little medicine factories, I became interested in using cells themselves as therapies and joined my current graduate program in Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at Stanford. Stem cells are a special subset of cells in the body that help in regeneration. For example, to replenish ageing red blood cells (RBCs) which have a four-month lifespan, the body produces about 200 billion RBCs every day – that’s about the same order of magnitude as the number of stars in the Milky Way! The source of new RBCs and other immune cells are hematopoietic stem cells, which reside in the bone marrow and last throughout a person’s life. With our understanding of human genetics, many diseases have been attributed to mutations at specific sites in the genetic code of our DNA. Mutations in the hemoglobin gene generate sickle shaped red blood cells that cannot transport oxygen efficiently, leading to sickle cell anemia. Similarly, changes in a gene sequence important for white blood cell development can cause immune disorders such as bubble boy disease. If we can correct gene mutations in patient stem cells and return them to the body, the patient should have a curative source of stem cells producing healthy blood cells. Within the last few years, biologists have learned from nature and developed a tool called CRISPR-Cas9 to precisely cut and insert sequences into a cell’s DNA. I am using this tool to develop a stem cell cure for a genetic autoimmune disease called IPEX syndrome [1]. But with the ability to precisely alter the genetic code, there have been questions of its societal ramifications and whether, from a religious standpoint, researchers are usurping God’s prerogative as Creator. Even before CRISPR technology, the movie Gattaca from 1997 raised such ethical concerns and describes a dystopian society where parents with access to technology can select the type of genes they want their children to have, creating two unequal classes of people in society. In reality, even a simple trait such as eye color is influenced by at least eight genes, and hundreds of genes may influence more complex traits such as height or intelligence. Since we do not fully understand the contribution of each gene to complex human traits and editing multiple genes is a technical challenge, the scenario described in the movie is unlikely. But the fact is that we can now genetically alter a person’s cells and return them to the body. It is also possible to alter the genetic make-up of human embryos that are then implanted, changing their genetic make-up and that of their future offspring.  These questions were important to me as a person of faith and became more urgent when in November 2018, it was announced that a scientist had gone ahead without proper consultation to edit the genomes of two embryos that then were implanted and became two baby girls [2]. While this was widely condemned by the scientific community – mainly on the grounds of the lack of transparency, questionable patient consent, and whether the procedure was a true medical need – it did not provide a satisfying response to the question of whether by making alterations to the code of life, medical researchers like me are ‘playing God’ and have overstepped our roles. I found my answer the following summer in the most unexpected of places while visiting a friend in Washington DC. We visited the US Capitol and one of its wings contains the Brumidi corridors [3] which at first looked like they were covered with standard wallpaper. Upon a closer look, each wall was painted with birds, plants, and scenery from a geological survey of the United States in the 1850s – it was one of the most beautiful insides of a building I’d ever seen! When I walked to the end of that corridor, however, I saw one corner of a wall that was extremely dull. Over hundreds of years, layers of dust had built up and tar from cigarette smoke that was once allowed in the Brumidi corridors stuck to the walls, causing these paintings to lose their original vibrancy. It was only after a restoration project that was completed in 2017 that these paintings began to shine again and the corner I saw had been left in its original state as a comparison.  I found the answer to my question – what I saw at the Capitol that day was a beautiful analogy for the work we are trying to do with CRISPR-Cas9 technology and stem cells, and also with the healthcare profession and medicine more broadly. The role of an art restorer is not to criticize the original masterpiece and change it by re-drawing the posture of the animals or adding new plants to spruce things up – it is merely to restore the painting which was already a masterpiece. It reminded me of a different part of Psalm 139 – that we are fearfully and wonderfully made by God, and our job is to restore those who are sick to live healthy and vibrant lives. Viewing gene editing and regenerative medicine through this new lens has given me a renewed sense of purpose in my work and provided a helpful framework that I use when considering new use cases for CRISPR and other medical technologies. Reflecting back, I see that God did not waste my interest in the field of medicine; he was using it in a different way. My vocation is training me to use science to help advance the field of medicine – which was something I did not appreciate when I faced rejection from medical school. God is not a vending machine for which, if I put in the correct format and length of prayer, the results I want are assured. We can plan our lives in a certain way, but it is God who determines our steps (Proverbs 16:9). I encourage you to trust Him because He is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to His power that is at work within us (Ephesians 3:20-21). If these themes resonated with you or you have more questions on gene editing and its implications, I would love to chat so please reach out to me at [email protected] Vendaprayers [5] References:

[1] Goodwin, M., Lee, E., Lakshmanan, U., Shipp, S., Froessl, L., & Barzaghi, F. et al. (May 2020). CRISPR-based gene editing enables FOXP3 gene repair in IPEX patient cells. Science Advances, 6(19), eaaz0571. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz0571 [2] Dennis Normile Chinese scientist who produced genetically altered babies sentenced to 3 years in jail. (Dec 30, 2019). Retrieved 15 August 2020, from https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/12/chinese-scientist-who-produced-genetically-altered-babies-sentenced-3-years-jail [3] Brumidi Corridors, Architect of the Capitol. (2020). Retrieved 15 August 2020, from https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/buildings-grounds/capitol-building/senate-wing/brumidi-corridors\ [4] Karlee R (Dec 21 2018) A doctored version of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam newly features a double helix connecting God and Adam, Emergent Concepts in New Media Art, Medium, Retrieved 16 August 2020, from https://medium.com/emergent-concepts-in-new-media-art/self-perception-28dbe9696ae0 [5] David Hayward (January 22 2014) If only pryer was this easy!, Retrieved 16 August 2020, from https://www.patheos.com/blogs/nakedpastor/2014/01/if-only-prayer-was-this-easy/  By Nathan Wei Ph.D. Candidate, Mechanical Engineering, Stanford University What is the world’s most epic story? One might argue for Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Perhaps it’s the Iliad, or the Epic of Gilgamesh. What about Shakespeare? Star Wars? War and Peace? The Marvel Cinematic Universe? As captivating as they are, a Christian perspective might suggest that all of these grand tales are simply faint reflections of the ultimate story of God’s work in the world. In classic Hollywood fashion, this is often framed as a trilogy: creation, fall, and redemption.1 For Christians, this is the most comprehensive story imaginable: it’s God’s story, our story, and the story of the entire course of history, all rolled into one magnificent, massive metanarrative.2 Accordingly, we can get pretty jazzed about the things God is doing on a cosmic scale: singing songs, shouting praises, celebrating holidays. But more often, that bigger picture feels far removed from the mundane routines of daily life: sending emails, attending meetings, doing laundry. Is there a way to bridge the gap? Can we relate our individual stories to God’s big story? The Concept of Square-Inch Stories Enter the square-inch story.3 The name draws inspiration from the declaration of Dutch theologian Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920): “No single piece of our mental world is to be hermetically sealed off from the rest, and there is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, ‘Mine!’”4 In this powerful proclamation, Kuyper emphatically erases the gap between our activities and God’s plans. While Christ reigns over the entire arc of human history, He also rules over every single square inch we inhabit.5 These square inches include our work, our vocation, our passions, our hobbies, our relationships, our communities, and our worldviews. Kuyper reminds us that Christ cares deeply about each and every one of these areas, as each has an immeasurably important part to play in His story.6 A square-inch story aims to actualize Kuyper’s vision by selecting one particular square inch and seeking to understand how it is connected with God’s greater plan. First, it identifies key patterns, processes, and philosophies within the square inch. It then critically examines these elements in light of the ultimate story, discerning which parts are good (creation), and which parts have been corrupted (fall). Finally, it reimagines these pieces as tools and materials for the building up of God’s kingdom (redemption). A square-inch story thus conveys a domain-specific expression of Christ’s vision for the renewal of all things. Before we consider how to put together a square-inch story, we should clarify why this complicated endeavor is worth our time. I offer three motivations: personal, ecclesial, and missional.7 First, on a personal level, the process of thinking through our disciplines helps us discover meaning and purpose within the seemingly mundane activities we perform in our square inches. This can strengthen our faith and help us submit all areas of our life to God’s will.8 Secondly, the Church is constantly in need of thoughtful narratives of reconciliation that restore square inches to proper relationship with the Body of Christ. For example, widely circulated stories about the incompatibility of Christian faith with the natural and social sciences have left many Christians suspicious of modern science. What would it look like if instead we told stories of the designated role of science in God’s redemptive plan?9 Finally, square-inch stories are inherently missional, because every story has the potential to connect with people in unique and meaningful ways.10 Since the Body of Christ is by design wonderfully diverse, each Christ-follower inhabits a different set of communities.11 Each of us therefore is uniquely positioned to engage with a particular group of people, as ambassadors of Christ to a particular square inch.12 The square-inch story helps us step into this role, by identifying areas of common ground with our neighbors and colleagues 13 and giving us the framework and vocabulary to tell God’s story in the language of the square inch.14 In accordance with its missional orientation, the structure of a square-inch story will largely be determined by the particular characteristics of the community it addresses. It may lean philosophical or practical, intellectual or relational. It may take the form of a talk, a blog post, a painting, or a composition. The specifics are up to the storyteller, but in all cases, the content is centered on connections between the square inch and the overarching metanarrative. The Construction of Square-Inch Stories We thus return to the practical question: how do we put together a square-inch story? As we have seen, the square-inch story draws substance from the three-part structure of the ultimate story. We can therefore begin thinking through our square inches by looking at their assumptions and practices through the lens of the story of Scripture, or in the words of Dr. Chris Watkin, “letting the Bible set its own table.”15 Creation. As in the ultimate story, we expect to find elements within our square inches that are inherently good and bear the hallmarks of God’s design. These can and should be affirmed and celebrated, such as the beauty of music or the intricacies of DNA. In this sense, the construction of a square-inch story is a process of exploration that leads to awe and worship.16 Fall. However, we should not be surprised to find areas within our square inches that have fallen away from God’s good plan. These often take the form of implicit assumptions embedded in the philosophy of a discipline that only become visible under the spotlight of Scripture. In many cases, these assumptions lie at the roots of systemic blind spots and unjust patterns of thought and action. The construction of a square-inch story is thus a critical endeavor that exposes the brokenness in a square inch and highlights its need for redemption.17 Redemption. With this brokenness as a backdrop, a square-inch story can ask how Christ will redeem the fallen aspects of the square inch and transform it into a place of worship, justice, and human flourishing.18 How can this field glorify God? How can this discipline seek justice and love mercy?19 How is Christ calling this community to serve those in need? There are no easy answers to these questions, but as we wrestle with them, we begin to see how our little square inch fits into God’s grand plan to make all things work together for good.20 The Continuation of Square-Inch Stories Creating a square-inch story requires a significant investment of thought and reflection, and it is not a project to tackle alone. Kuyper himself, referring to the academic application of square-inch theology, said that this is a “task which surpasses our human strength.”21 It requires wisdom from the Holy Spirit, guidance from Scripture, and support, encouragement, and correction from Christian community. Furthermore, the construction of a square-inch story does not end with the completion of an article or talk. It is a lifelong process that we undertake for every square inch we find ourselves in, and our work is not complete until the whole domain of human existence sits obediently before the throne of God. With this humbling perspective in mind, I shall close in the great academic tradition of pointing to future work. In the square-inch stories that follow in this series, you will see a variety of explorational forays into the Kuyperian enterprise – square-inch seedlings, if you will, putting down roots into their particular disciplines and communities, and stretching themselves upward toward the light of Christ. You will hear from students and scholars who are learning to become better storytellers and translators for their colleagues and contemporaries. And I hope you will be inspired by their testimonies to take a closer look at the domains you engage with – because every square inch has an indispensable role to play in the world’s most epic story. Recommended Resources

Many thanks to Andrea Chaikovsky, Carissa Wei, Jonathan Love, Joy Chiew, Katie Ferrick, and Kristel Tjandra for providing feedback on this article, and to the members of the Stanford IVGrad Square-Inch Discussion Group for collectively shaping the vision for this project. Footnotes: 1 Trevin Wax, Counterfeit Gospels: Rediscovering the Good News in a World of False Hope (2011). Wax adds a fourth and final element, restoration (or consummation), which is ‘beyond the scope of this work.’ 2 A metanarrative is an overarching story that serves as a framework for the interpretation of ideas or events. 3 “Square-centimeter story” is scientifically more correct, but it doesn’t roll off the tongue quite as nicely. 4 Abraham Kuyper, “Sphere Sovereignty” (1880). Address at the Free University of Amsterdam. Translation available here. 5 Kuyper called these “spheres”, but to be metaphorically and geometrically consistent, I conflate his idea of sphere sovereignty with the square-inch declaration quoted above. The man himself inhabited several of these spheres, as a theologian, journalist, academic, politician, and statesman. See this blog post for a more detailed discussion. 6 This idea did not necessarily originate with Kuyper. For instance, the English bishop Joseph Hall (1574-1656) is noted for saying with regard to secular work that “God loveth adverbs; and cares not how good, but how well” (cf. Nicholas Wolterstorff, Educating for Shalom, p. 270). 7 Tish Harrison Warren, in her contribution to Uncommon Ground: Living Faithfully in a World of Difference (Timothy Keller and John Inazu, eds.), writes, “This intentional practice of, in the words of Luci Shaw, “telling and retelling the story that weaves together divine transcendence and earthly human experience” shapes us as believers, and it shapes our readers” (p. 80). Her essay underscores the importance of communication: “our words shape our practices, just as practices shape our words” (p. 80). 8 Colossians 3:17. It is also worthwhile to consider reason and critical thinking as spiritual disciplines. Enoch Kuo (who first introduced me to Kuyper) elaborates on this idea in this blog post. He draws from Mike Higton’s A Theology of Higher Education, which is a useful reference for this topic and for Christian engagement in a university context. 9 An excellent example of this kind of story is The Language of God by Dr. Francis Collins. 10 An emphasis on stories is increasingly relevant as our society transitions from a postmodernist worldview to a “metamodernist” one, in which meta-narratives are empowered as catalysts for progress and unity. In this philosophical landscape, the square-inch story becomes even more crucial to maintaining an effective Christian witness. 11 Dr. Katharine Hayhoe, a renowned climate scientist and outspoken evangelical Christian, frequently emphasizes the influence we can have on the individual communities we find ourselves in. Here, she discusses this in relation to environmental advocacy, but her ideas are readily generalizable. 12 2 Corinthians 5:18-20. 13 Acts 17:22-34. 14 Acts 2:6-12. For a much more comprehensive discussion of the Christian’s role as translator, see John Inazu’s essay in Uncommon Ground. 15 Dr. Chris Watkin was our invited speaker at the annual InterVarsity NorCal Grad Student Winter Conference in January 2020. His talks provided the inspiration, vocabulary, and theological framework for this project. Links to the talks can be found on his blog, “Thinking Through the Bible.” 16 There is great precedent for this in Scripture (e.g. Psalm 19:1-6, Proverbs 30:24-28), as well as in the history of Christian thought. In my own research, I am constantly in awe of the intricate motions of fluid flows and the mathematical concept of chaos, both of which are powerful recurring themes in the Bible. 17 Nicholas Wolterstorff writes that Christians should “nourish critique that is shaped by the hopes and memories of the biblical narrative, including then, ethical critique of the practices of society generally” (Educating for Shalom, p. 130). This critique is driven by “the faces and voices of those suffering in our world”, since “an ethic that does not echo humanity’s lament does not merit humanity’s attention” (p. 133). 18 This perspective of Christian engagement with aspects of secular culture reflects H. Richard Niebuhr’s paradigm of “Christ transforming culture” from his influential book Christ and Culture (1951). In the wise words of Wolterstorff: "To serve God faithfully and to serve humanity effectively, one has to critique the received role [i.e. our square inch] and do what one can to alter the script" (Educating for Shalom, p. 272). 19 Micah 6:8. 20 Ephesians 1:9-10. 21 Abraham Kuyper, “Sphere Sovereignty.” |

AuthorContributions are from various grad students throughout our area. There are a wide variety of thoughts and beliefs within our community, but we strive together to engage in reflective conversation with the common goal to seek Jesus. Archives

March 2021

Categories |

|

Copyright © InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed